Katharina Sieverding

On "Deutschland wird deutscher" (1992)

Home in Berlin and very happy about it. The city feels romantically hard-edged. I go to Jivamukti to stretch and chant, listen to Deutschpop from 2005 while roaming around Kreuzberg, blast Ikkimel as I disappear into the U6 (fully Caro’s fault), and sing along to every single song on the—profoundly great—new Miley Cyrus album as I cycle through the night. Proqm has already received a significant amount of my income for this month, so have various Spätis around Neukölln with a ten euro credit card minimum. On Sunday, I watched the sunset outside Berghain and later sat opposite a teenage couple on the bus with very cinematic faces (more Bruno Dumont than Eric Rohmer).

It’s a whole life, beautiful in the way of fleeting things.

While all of the above is happening, what I really should be doing is prepare for General Exams (capitalized to highlight their profound importance as the determining launchpad of my academic career). There has been some blockage around this imperative, mostly because I hate to feel like a show pony getting ready for one big audacious jump in exchange for a pretty sash. What I want from these exams is to actually thicken the intellectual substrate I exist in, to enjoy the process, to feel alive within it. And what better way to achieve aliveness than to make sure it’s all documented on the internet! At least that is what Berlin’s aggressively instagrammable art crowd seems to be telling me.

So here we go, the inaugural edition of my art column. Centered on single artworks! How very art history of me. Call me the Carrie Bradshaw of criticism. I couldn’t help but wonder… why I cannot get Katharina Sieverding out of my head.

I want to say that Deutschland wird deutscher, Katharina Sieverding’s black-and-white photo print, is a violent artwork. The phrase, which translates to “Germany becomes more German,” is just a sliver away from its outright xenophobic counterpart “Deutschland den Deutschen,” Germany to the Germans. Both ring in my ears in the voices of Goebbels, Weidel, Schlägertrupps, a despicable chorus of people who grin like idiots at dogs and toddlers but are fundamentally suspicious of anyone who has evolved towards the management of their own fecal matter.

Alas, I have to admit that the sentence is highly sayable. It has a ring to it, the rhythmic appeal of a slogan. There may be such a thing as violent seduction, embodied in the desire manufactured by truly relentless advertisement. Warhol would have put: Drink Coca-Cola, and it would have carried the same erotic charge.

What is a violent artwork? The poster does not inflict harm on anyone, not even in the way a caricature can hurt someone’s sense of self, or a gory image of death tears a traumatic hole into the fabric of reality. When I say “violent,” I am referring to the way in which Sieverding’s work relates to the viewer: it confronts and hits; grabs by the neck and doesn’t let you off the hook. Instead of offering poetically ruminative interventions into public discourse and visual drudgery, Sieverding doubles down on a climate of confrontation, interspersing public space with an image as piercing as the throwing knives it depicts.

The climate of confrontation into which Deutschland wird deutscher emerged were the 1990s in Germany, retrospectively deemed Baseballschlägerjahre, baseball bat years, for the many violent attacks by neo-nazis that happened in Rostock, Hoyerswerda, Solingen, uncountable elsewheres.

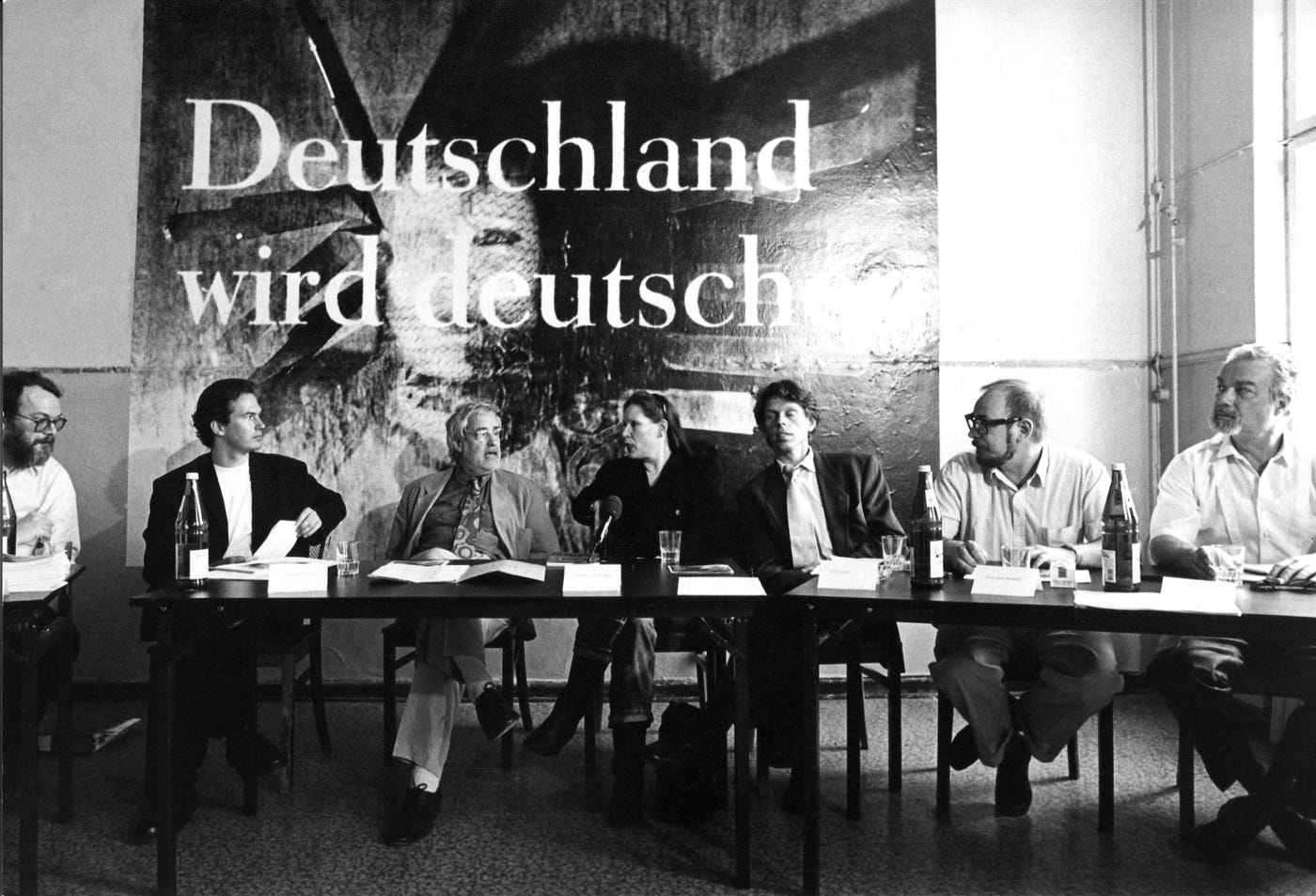

Sieverding initially conceptualized Deutschland wird deutscher as a series of posters to be displayed in Baden-Württemberg, where the project was met with protests and finally fell through. Instead, Kunst-Werke Berlin took over stewardship of the project and ensured distribution throughout the city.

The work has since been reissued for acquisition by museums and collectors, but it retains a former life among advertisements and government campaigns, instruments of commerce and information. Compare this initial reception context to the encounter with a photograph in a museum: there, the image exists foremost as an object for aesthetic pleasure or a catalyst of critical scrutiny, in any case more lucid, self-reflective beholding than the way a public poster drills itself into the subconscious.

Much of Sieverding’s work is, I think, probing a pathway into the deeper, darker realm where images live. That realm is not quite an archive—too institutional, too bureaucratic. The visual archive of German national identity contains Willy Brandt getting down on his knees in Warsaw, Breschnew’s and Honecker’s kiss on the lips, Merkel carving a Dönerspieß, the dead bodies at Stammheim, at Auschwitz. These are by no means simplistic images, but I would venture to say that they possess the narrative grammar of history painting, cataloguing pregnant moments of significance and revelation. Instead of offering clarity, Deutschland wird deutscher thickens repressed energies, undercurrents that are always there but can’t quite be captured by a single event.

That realm I am talking about may be: a basement. Every time I look at Deutschland wird deutscher, with its violently sexual charge of a woman reduced to shadows and under attack, I think of a scene in Christian Kracht’s novel Eurotrash (2021), wherein the narrator describes the BDSM torture chamber underneath the villa his grandfather, former Nazi turned respectable uppercrust Bundesrepublikaner, owns on the glitzy island of Sylt:

And I saw the collection of sadomasochistic paraphernalia discovered after his death, in the bolted wardrobe of the guest room in his home on the island of Sylt, that tawdry arsenal of degradation which this old man, my grandfather—party member since 1928, Untersturmführer in the SS and employed by the Reichspropagandaleitung of the Nazis in Berlin—had gathered in his home on Sylt after the war and after the, alas, complete failure of his denazification process in the British internment camp Delmenhorst-Adelheide, and which he had made use of, if not in reality, then most certainly in sweaty reverie, during clandestine cellar trysts with the young au pairs he hired from Iceland.

Deutschland wird deutscher could be a snapshot of this “sweaty reverie,” if those perfectly Aryan girls from Iceland had come into the possession of a camera, and turned the old man’s desire against himself by creating an image that looks back.